I Need to Talk to Someone about The Journal of Albion Moonlight

I have to wonder if anybody can read Kenneth Patchen's experimental novel, The Journal of Albion Moonlight, (1941), and not immediately want to talk to somebody about the experience. It's a novel only in the very broadest sense, meaning that it has magnitude, and characters who persist in orbiting around the terrible title character, Albion, throughout, and a plot of sorts involving an action moving randomly all over the US and also onto the WWII battlefields of Europe. Perhaps the most important thing to note about Albion and his life and times, which Patchen makes clear, is that no part of his story is real. For one, Albion dialogues with most of the cows he meets. So that means he's also not really doing these awful things. He signals this by frequently having the characters assault or kill each other or be murdered by each other, and then, a chapter later, springing back to life, only to die again later on. Albion himself commits any number of atrocities, but his victims almost always turn up again later, unharmed. Tropic of Cancer author Henry Miller wrote of his deep admiration in a 1946 essay titled "Kenneth Patchen: Man of Anger and Light," the preface to one of Patchen's books. In it, he talks about Patchen's impressive output, back surgeries, and poverty. "He works on two or three books at once," Miller says. "He labors in a state of almost unremitting pain. He lives in a room just about big enough to hold his carcass, a rented coffin you might call it, and a most insecure one at that. Would he not be better off dead?" Like Miller's preface, Patchen's novel is largely a diatribe against the many sponsors of the Second World War, and he includes all the world powers in his indictment, not just Adolph Hitler.

As I read, I was stunned to realize it was written in 1941. There really were no other American writers so flagrantly violating the tenets of the latest movement in art, Modernism, which was only recently formalized and put into practice on our shores in about 1919 when Sherwood Anderson's story collection, Winesburg, Ohio, came out. Patchen's attack on the world powers for allowing a war that was mostly killing children -- boy-children -- was so venomous that Delmore Schwartz convinced Patchen's quite radical publisher, New Directions, to drop the book like a hot potato -- so it didn't finally appear with their imprint until 20 years later, in 1961. Patchen produced a prodigious number of literary books, mostly by New Directions, and several posthumous works appeared via small and micro-presses. He did paintings for dozens if not hundreds of book covers and engaged in musical collaborations with no less than John Cage and Charles Mingus.

The novel is held together by a fragile plot employing Albion's shape-shifting associates with names such as Billy Delian, Thomas Honey, an African-American character named Jetter, Joseph Gambetta, Albion's wife, Carol, and the couple's daughter, Jackeen, who is only thirteen. The whole Canterbury Tales-like parade of oddballs appears to be on some long, terrible road trip. The action may either be hopping from roadhouse to flophouse to bordello across the entire country or the party may never get west of Galen, NY. Along the way, Albion is rolling in and out of bed with an ensemble of interchangeable women named Jenny, Mildred, Ann, Margaret, Martha, etc, etc, but he doesn't truly desire any female except Jackeen who he can't have. One of the many unsettling things about the novel is how some passages resemble the ecstatic ramblings of Kerouac's On The Road which won't be published for another 17 years. Albion even says he wants his book to be written as it happens -- a quality Kerouac also strived for. He says he's trying to make a book he can read for the first time after he writes it. Albion's cringe-y raptures over his nymph-like daughter actually seem to foretell a book titled Lolita by Nabokov, which won't appear for another 14 years. Albion also has a habit of coming to suddenly in the middle of a gory bombardment on a European battlefield, not unlike Vonnegut's time-and-space-traveling hero, Billy Pilgrim, from Slaughterhouse Five, which won't be coming for another 28 years. The book could also be viewed as a shock-and-awe, death-metal version of The Journals of Lewis and Clark. Years before Jackson Pollock has really come onto the abstract art scene with his dribble method, Albion encounters a flock of parrots and one says to him "The painter will strive to exclude all living images from his canvases. He will paint only that which cannot be seen." Albion even seems to anticipate the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, coming in just a few years, when he asks "How can any man sign the death warrant of millions of his fellows?"

Albion's quest throughout includes an anguished striving towards a confrontation with a fugitive celestial named Roivas (Savior spelled backward) who, when found at last, is so hideous It can hardly be looked upon. Patchen arrives early at a possible thesis for his story (page 90) when he writes "Capitalism and Fascism are one under the iron mask. Fascism is the expression of Capitalism's death struggle. War is the life blood of Capitalism." Patchen confesses eventually (p 116) that his attitude toward the people in his story is that of "a monster cat in a box of mice." He then makes sport of conventional novels (p 147) by writing "A certain man in a certain town has a certain affair with a certain woman . . . and what part does Caleb Middlepot have in all this or/and just how strong is love and/or why was there a petunia in the dead man's hand . . . " On this insane pilgrimmage, Hitler and Christ are characters in a drama for perhaps the first time in American letters. Cannibalism is also featured. Calendar dates, normally orienting for the reader of someone's diary, come and go at random. There is a horrible mine explosion which I paid attention to because I had a great uncle killed in just such a disaster. He tries to end the novel for the first time on page 169 but it still has another 144 pages to go. In fact, perhaps the most novel-like quality of this novel is that Patchen keeps trying to end it but can't seem to figure out how.

We enter a realm of the book called The Notes on page 216 and Patchen seems to begin reeling off the random contents of his consciousness, including long lists of "I am" statements about what he believes to be true ("My book is babbling junk") and some writing tips: "get rid of all charm." "Manage at the last to crowd out all of the book's characters." He even critiques language itself saying "The word is the thing the wind says to the dead." And the classics: "No one in Proust ever interested me as much as the people who happened to be in the room . . ." Near the end, page 298, Patchen, speaking through his alter-ego Albion, very aptly states the major tenet of Post-Modernism: "I mean that there are as many worlds as there are human beings. And because of this, there is only one world . . . " Here again, Patchen has given shape to an artistic outlook that won't achieve full expression in literature until the Beat writers begin to appear in the early 1950s, which is saying something. If you decide to read it, brace yourself.

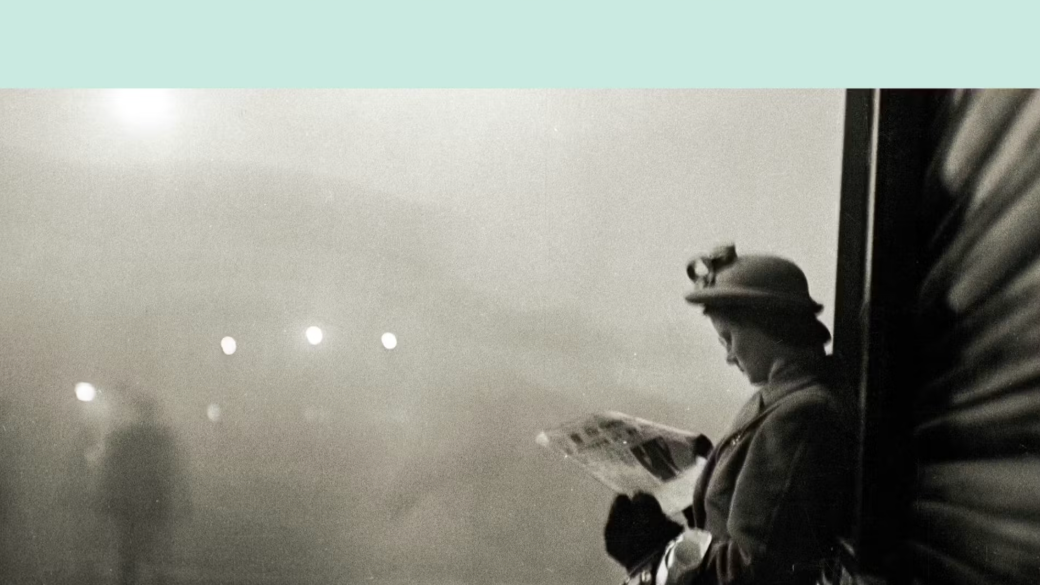

Another much more popular book to consider this time is Margery Allingham's 1952 thriller and masterpiece, The Tiger in the Smoke, about a time in London when the city was simply called The Smoke because of the cloud of chimney smoke a half-mile high and twenty miles across, blanketing the streets and making it a haven for pickpocketing, burglary, and knife-crimes. The time is five years after the Blitz and the evil one or tiger is a war veteran who recently escaped prison and calls himself Jack Havoc, but whose real name is Johnny Cash. But it's just a funny coincidence since Allingham had never heard of the singer when writing the book. In the war, Havoc met a soldier who spoke of a treasure hidden in a French cottage once owned by his family, but he is then blown up by a landmine before divulging the exact location or the kind of booty. But it's possible the girl-he-left-behind may also know the secret.

A movie I like this time is It Was Just An Accident, about an unlikely grouping of recently-released detainees of the Iranian regime who learn that a man resembling a sociopathic prison guard nicknamed The Gimp is now living and working at a civilian job right in their own neighborhood.

For any new readers: My novel, Tania the Revolutionary, is available on Amazon for Kindle and paperback or Barnes & Noble for eBook.